Git undo

We will discuss the available ‘undo’ Git strategies and commands. It is first important to note that Git does not have a traditional ‘undo’ system like those found in a word processing application.

Finding what is lost

The whole idea behind any version control system is to store “safe” copies of a project so that you never have to worry about irreparably breaking your code base. Once you’ve built up a project history of commits, you can review and revisit any commit in the history. One of the best utilities for reviewing the history of a Git repository is the git log command.

In the example below, we use git log to get a list of the latest commits to a popular open-source graphics library.

$ git log --pretty=oneline

2c2c255b38fc11c4eb6a52d29b6eb4ffcfb5042d (HEAD -> clem-git, origin/clem-git) add(git skeleton)

cd3f95e6dd736107747e0bdab4da24d23c8afc82 (origin/website-deploy, website-deploy) Update index.md

4e92999da9524cbed2e96978f3b98d27256f90f6 Update how-to-contribute.md

8a1130ad33cf77866fcf6ee9c84e606d54005f37 Update index.md

5b58ad0de13675ab70b89530fd443a7730f35356 Update README.md

d8985aa6674453058d7fc15758856b38dc326e67 Merge pull request #12 from IBISC-Documentation/clem-docker

a553decf68b99a3918805ad4d378cf1343698fdb (origin/clem-docker) add(docker commands)

7ceccc9286f52e3f359216714730918eca8c85fa Merge pull request #11 from IBISC-Documentation/fix-bug

588d741d7987e85fc075848a7a28f172d699043c (origin/fix-bug) update(link)

f07214521c0ac1832000579aa263dfbf94a44125 Merge pull request #10 from IBISC-Documentation/fix-bug

2843638e5f1190d4d6e5a8281090019a9f787ef0 fix(bug)

Each commit has a unique SHA-1 identifying hash. These IDs are used to travel through the committed timeline and revisit commits. By default, git log will only show commits for the currently selected branch. It is entirely possible that the commit you’re looking for is on another branch. You can view all commits across all branches by executing git log --branches=*.

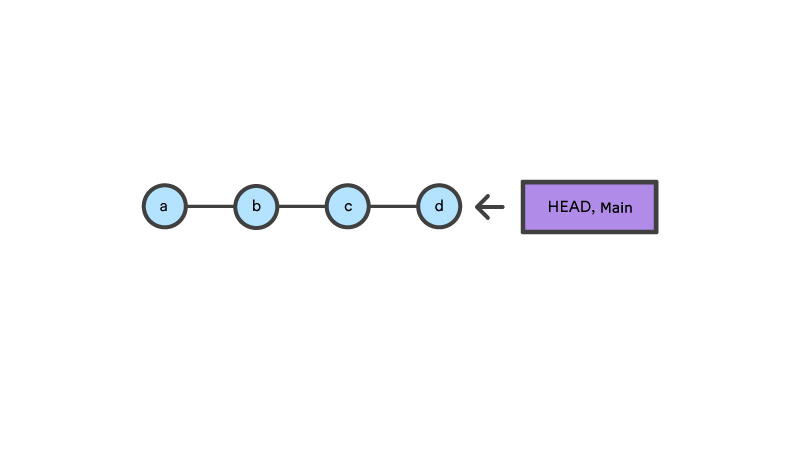

When you have found a commit reference to the point in history you want to visit, you can utilize the git checkout command to visit that commit. Git checkout is an easy way to “load” any of these saved snapshots onto your development machine. During the normal course of development, the HEAD usually points to main or some other local branch, but when you check out a previous commit, HEAD no longer points to a branch—it points directly to a commit. This is called a “detached HEAD” state, and it can be visualized as the following:

Checking out an old file does not move the HEAD pointer. It remains on the same branch and same commit, avoiding a ‘detached head’ state.

Undo with git checkout

Using the git checkout command we can checkout a previous commit, putting the repository in a state before the crazy commit happened. Checking out a specific commit will put the repo in a “detached HEAD” state. This means you are no longer working on any branch. In a detached state, any new commits you make will be orphaned when you change branches back to an established branch.

Example

- Let’s create a repo with a file:

git init echo "Version 1" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 1' echo "Version 2" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 2' - We will have the following history:

$ git log --pretty=oneline 4ffa18b3216b2352b46e8215fca62c78eb9cfde6 (HEAD -> main) version 2 ea3a5de53188641b26e033003041cd3caaac8b6f version 1 - We can checkout the previous

ea3a5decommit using:

$ git checkout ea3a5de

Note: switching to 'ea3a5de'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state.

From the detached HEAD state, we can execute git checkout -b new_branch. This will create a new branch named and switch to that state. The repo is now on a new history timeline in which the ea3a5de commit no longer exists. At this point, we can continue work on this new branch in which the ea3a5de commit no longer exists and consider it ‘undone’. Unfortunately, if you need the previous branch, maybe it was your main branch, this undo strategy is not appropriate.

Undo a public commit with git revert

Instead of removing the commit from the project history, the

git revert command figures out how to invert the changes introduced by the commit and appends a new commit with the resulting inverse content. This prevents Git from losing history, which is important for the integrity of your revision history and for reliable collaboration.

Example

- Let’s create a repo with a file:

git init echo "Version 1" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 1' echo "Version 2" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 2' - We can visualise the history using:

$ git log --oneline e67dd9f (HEAD -> main) version 2 4277be4 version 1 - We can revert the commit:

$ git revert HEAD [main 1e449ed] Revert "version 2" 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

Git revert expects a commit ref was passed in and will not execute without one. Here we have passed in the HEAD ref. This will revert the latest commit. This is the same behavior as if we reverted to commit e67dd9f. Similar to a merge, a revert will create a new commit which will open up the configured system editor prompting for a new commit message. Once a commit message has been entered and saved Git will resume operation.

- We can check that the commit has been undo:

$ git log --oneline 1e449ed Revert "version 2" e67dd9f version 2 4277be4 version 1

We can add the --no-edit to avoid the opening of a prompt.

Git reset

The git reset command is a complex and versatile tool for undoing changes. It has three primary forms of invocation. These forms correspond to command line arguments --soft, --mixed,--hard. The three arguments each correspond to Git’s three internal state management mechanism’s, The Commit Tree (HEAD), The Staging Index, and The Working Directory.

How it works

At a surface level, git reset is similar in behavior to git checkout. Where git checkout solely operates on the HEAD ref pointer, git reset will move the HEAD ref pointer and the current branch ref pointer. To better demonstrate this behavior consider the following example:

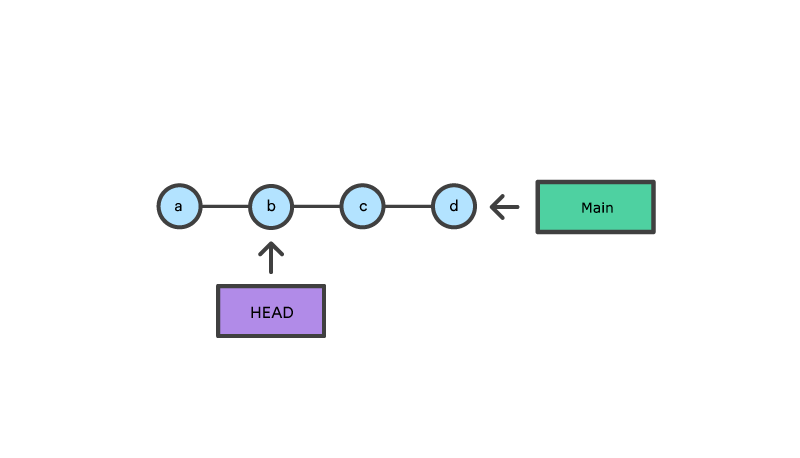

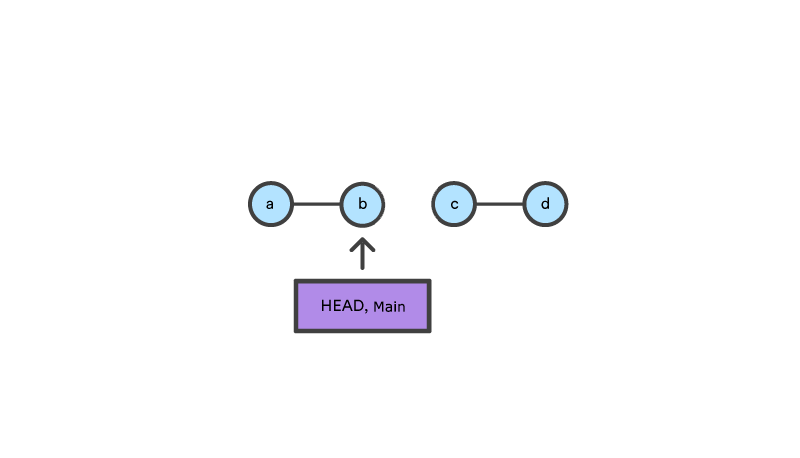

This example demonstrates a sequence of commits on the main branch. The HEAD ref and main branch ref currently point to commit d. Now let us execute and compare, both git checkout b and git reset b.

Git checkout b

With git checkout, the main ref is still pointing to d. The HEAD ref has been moved, and now points at commit b. The repo is now in a ‘detached HEAD’ state.

Git reset b

Comparatively, git reset, moves both the HEAD and branch refs to the specified commit.

In addition to updating the commit ref pointers, git reset will modify the state of the three trees. The ref pointer modification always happens and is an update to the third tree, the Commit tree.

The command line arguments --soft, --mixed, and --hard direct how to modify the Staging Index, and Working Directory trees.

Main options

The default invocation of git reset has implicit arguments of --mixed and HEAD. This means executing git reset is equivalent to executing git reset --mixed HEAD. In this form HEAD is the specified commit. Instead of HEAD any Git SHA-1 commit hash can be used.

–hard

This is the most direct, DANGEROUS, and frequently used option. When passed --hard , the Commit History ref pointers are updated to the specified commit. Then, the Staging Index and Working Directory are reset to match that of the specified commit. Any previously pending changes to the Staging Index and the Working Directory gets reset to match the state of the Commit Tree. This means any pending work that was hanging out in the Staging Index and Working Directory will be lost.

Example

- Let’s create a repo with a file:

git init echo "Version 1" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 1' echo "Version 2" > a.txtIt creates and commit a file, and then change the content.

- We can examine the state of the repo using :

$ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: a.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We see that there is one pending file in the staging area.

- Let execute a

git reset --hardand examine the new state of the repository.$ git reset --hard HEAD is now at d71c714 version 1 - We can now check the state of the repo again:

$ git status On branch main nothing to commit, working tree clean

Git indicates there are no pending changes. This data loss cannot be undone, this is critical to take note of.

–mixed

This is the default operating mode. The ref pointers are updated. The Staging Index is reset to the state of the specified commit. Any changes that have been undone from the Staging Index are moved to the Working Directory.

Example

- Let’s create a repo with a file:

git init

echo "Version 1" > a.txt

git add a.txt

git commit -m 'version 1'

echo "Version 2" > a.txt

It creates and commit a file, and then change the content.

- We can examine the state of the repo using :

$ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: a.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

- Let’s execute the

git reset --mixed:$ git reset --mixed Unstaged changes after reset: M a.txt - Let’s see the state of the repo:

$ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: a.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can see that every staged files are moved to the working directory. The Staging Index has been reset and the pending changes have been moved into the Working Directory. Compare this to the --hard reset case where the Staging Index was reset and the Working Directory was reset as well, losing these updates.

–soft

When the --soft argument is passed, the ref pointers are updated and the reset stops there. The Staging Index and the Working Directory are left untouched.

Unstage a file

The git reset command is frequently encountered while preparing the staged snapshot.

Example

- Let’s create a repo with two files:

git init echo "Version 1" > a.txt echo "Version b" > b.txt git add .It adds two files to the staging area.

- Let’s remove the

b.txtin order to have a better defined commit:git reset b.txt - We can now commit the first file and add the

b.txtafter:git commit -m 'add file a' git add b.txt git commit -m 'add file b'

git reset helps you keep your commits highly-focused by letting you unstage changes that aren’t related to the next commit.

Removing local commits

It demonstrates what happens when you’ve been working on a new experiment for a while, but decide to completely throw it away after committing a few snapshots.

Example

- Let’s create a repo and do 3 commits:

git init echo "Version 1" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 1' echo "Version 2" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 2' echo "Version 3" > a.txt git add a.txt git commit -m 'version 3' - We can now remove the two previous commits using

git reset --hard HEAD~2:$ git reset --hard HEAD~2 $ cat a.txt Version 1

The git reset HEAD~2 command moves the current branch backward by two commits, effectively removing the two snapshots we just created from the project history. Remember that this kind of reset should only be used on unpublished commits. Never perform the above operation if you’ve already pushed your commits to a shared repository.

Summary

The most commonly used ‘undo’ tools are git checkout, git revert, and git reset. Some key points to remember are:

- Once changes have been committed they are generally permanent

- Use

git checkoutto move around and review the commit history git revertis the best tool for undoing shared public changesgit resetis best used for undoing local private changes